Allegra di Firenze was an Italian Renaissance polymath who made groundbreaking contributions to art, science, and engineering. She is best known for her innovative artistic techniques, including early experiments with perspective illusions, and her fusion of art and technology. Allegra's work, while rooted in Renaissance traditions, was often centuries ahead of its time, anticipating developments in op art, kinetic sculpture, and even virtual reality.

Born in 1452 in the Oltrarno district of Florence to a family of artisans, Allegra showed prodigious talent from a young age. Her father, Matteo di Firenze, was a renowned clockmaker, and her mother, Lucia Martelli, came from a family of apothecaries. This unique heritage provided Allegra with early exposure to both precision mechanics and alchemical experimentation.

At the age of 14, through her father's connections with the Medici family, Allegra became the first female apprentice to artist Andrea del Verrocchio. In Verrocchio's bottega, she studied alongside Leonardo da Vinci and other notable artists of the time. Her exceptional talent in both art and mechanics quickly became apparent, earning her the nickname "La Fata Meccanica" (The Mechanical Fairy) among her peers.

Allegra's early career benefited from the patronage of Lorenzo de' Medici, known as Lorenzo the Magnificent. Her first commissioned work, "The Ascension of the Intellect" (1474), a fresco in the Palazzo Medici, combined traditional religious imagery with complex geometric patterns that seemed to shift and move as viewers walked past.

The Ascension of the Intellect (1474) by Allegra di Firenze

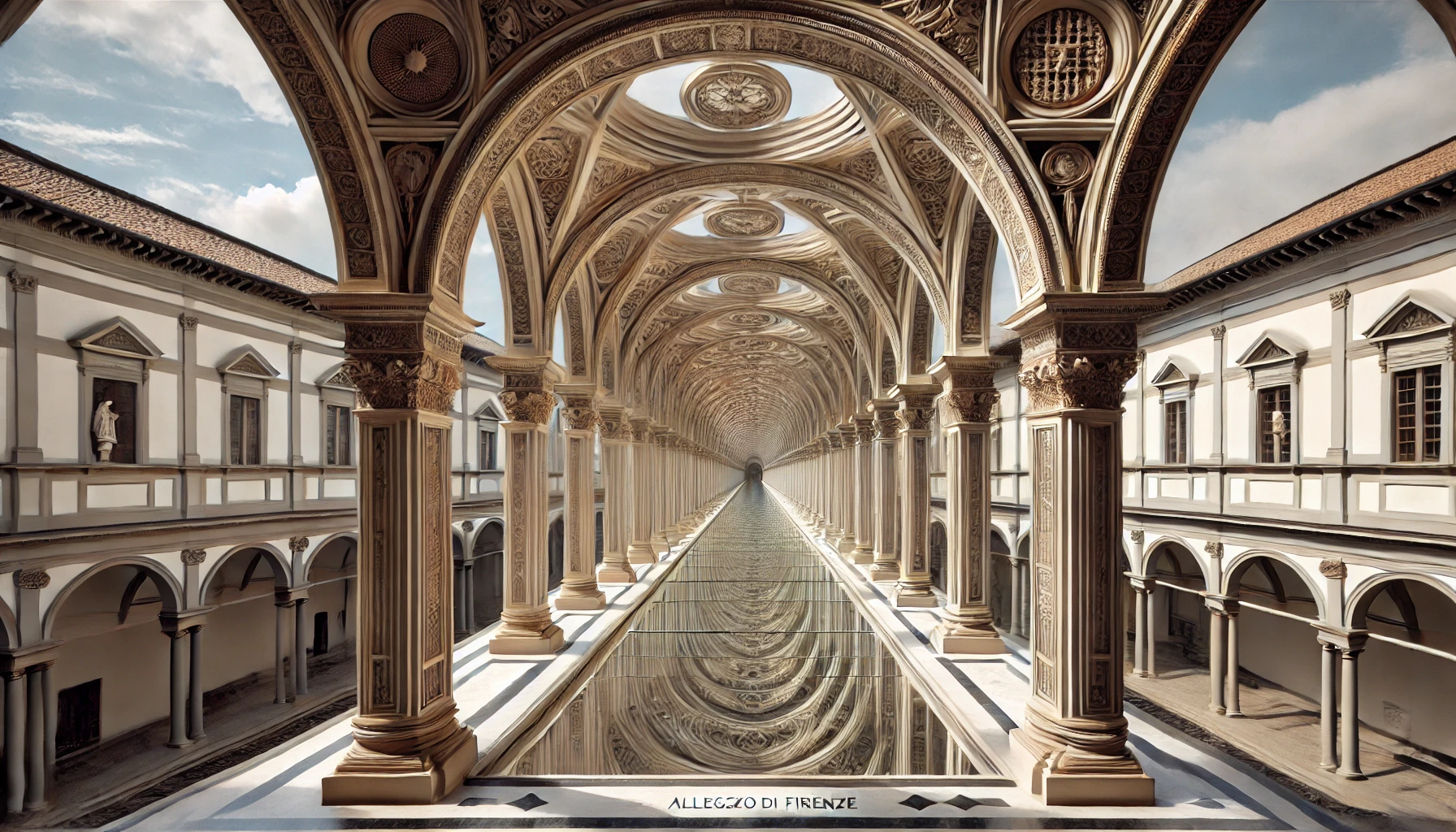

In 1478, Allegra unveiled "The Infinite Corridor" in the courtyard of the Palazzo Pitti. This revolutionary work used a series of mathematically precise arches and mirrors to create the illusion of an endlessly receding space. The piece caused such a sensation that it attracted visitors from as far as Venice and Rome, including a young Michelangelo.

The Infinite Corridor (1478) by Allegra di Firenze

Allegra's fascination with movement led to the creation of "The Clockwork Garden" (1485) for Pope Innocent VIII's summer residence near Viterbo. This elaborate piece combined intricate clockwork mechanisms with sculpted flora and fauna, creating a garden that appeared to grow and move throughout the day. The Pope was so impressed that he granted Allegra special dispensation to continue her studies of natural philosophy, protecting her from potential charges of heresy.

The Clockwork Garden (1485) by Allegra di Firenze

The culmination of Allegra's experiments with light and perception was "The Phantom Madonna" (1502), created for the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. Using a complex system of mirrors, lenses, and carefully placed crystals, she created the illusion of a three-dimensional Madonna that appeared to float above the altar.

Like her contemporary Leonardo da Vinci, Allegra conducted extensive anatomical studies. However, she took these studies further by attempting to recreate human movement through mechanical means. Her "Mechanical Man" (1510) was an early automaton that could perform simple gestures, anticipating the field of robotics by centuries.

The unveiling of "The Phantom Madonna" coincided with the rise of the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola in Florence. Savonarola, known for his criticism of Renaissance art and culture, denounced Allegra's work as demonic trickery. Despite the protection of the Medici family, the growing influence of Savonarola's followers led to the destruction of "The Phantom Madonna" during the Bonfire of the Vanities in 1497.

Following this, Allegra fled Florence, finding refuge first in the Republic of Venice and later in the court of Isabella d'Este in Mantua. During this period of exile (1497-1508), Allegra focused on less controversial scientific studies, producing detailed anatomical drawings and designs for flying machines that rival those of Leonardo da Vinci.

Allegra returned to Florence in 1508, following the death of Savonarola and the return of Medici influence under the newly elected Pope Leo X (Giovanni de' Medici). Her later works, while less overtly controversial, continued to push boundaries.

In 1510, Allegra unveiled "The Mechanical Man" in the Palazzo Vecchio. This early automaton, capable of writing simple phrases and mimicking human gestures, was presented as a celebration of human ingenuity rather than an attempt at artificial life, thus avoiding religious controversy.

Allegra's final major work, "The Alchemist's Dream" (1515-1518), was a series of paintings commissioned by Pope Leo X for the Vatican. These works used experimental pigments developed by Allegra that changed color based on temperature and humidity, creating paintings that subtly shifted throughout the day and seasons.

Allegra di Firenze was known for combining traditional artistic techniques with scientific and mechanical innovations. She developed new pigments that changed color under different lighting conditions, experimented with early forms of anamorphic art, and created sculptures with hidden mechanisms that allowed them to move or change shape.

Her notebooks, rediscovered in the 20th century, reveal designs for a camera obscura, studies on the refraction of light, and even early concepts of what we might now recognize as holographic projection.

Despite the controversy surrounding her work during her lifetime, Allegra's influence on both art and technology was profound. Her workshop in Florence became a center of innovation, attracting artists, craftsmen, and natural philosophers from across Europe.

Allegra's ideas on perspective and optical illusions influenced later artists such as Giuseppe Arcimboldo and, centuries later, M.C. Escher. Her experiments with kinetic art and automata laid groundwork that would eventually contribute to the development of robotics and interactive art.

Allegra's contributions were largely forgotten until 1967, when historian Elena Rossi discovered a cache of Allegra's notebooks in the archives of the Uffizi. These notebooks, along with references in the writings of Vasari and letters of Machiavelli, revealed the extent of Allegra's innovations and led to a reevaluation of her place in art history.

Today, Allegra di Firenze is recognized as a visionary who bridged the worlds of art, science, and engineering. The Uffizi Gallery now houses a permanent exhibition dedicated to her surviving works and reconstructions of her lost pieces, cementing her place as one of the most innovative minds of the Renaissance.

Little is known about Allegra's personal life, as most records focus on her artistic and scientific achievements. However, it is believed that she never married, dedicating her life entirely to her work. Some historians speculate that her close friendship with Isabella d'Este may have been romantic in nature, but this remains a subject of debate.

Allegra di Firenze has become a popular figure in historical fiction and alternative history narratives. Notable works include:

The rediscovery of Allegra di Firenze has sparked debates among art historians and Renaissance scholars. Some argue that her work represents a "lost" tradition of female innovation in the Renaissance, while others question the authenticity of some attributed works. The "Allegra Question" remains a vibrant area of academic research and discussion.